Integration Tests Can Be Fun!

One of the most mundane and frightening tasks for many developers is writing integration tests. It’s a time-consuming, fragile, and often difficult and frustrating task to accomplish. What makes it even worse is that it quickly gets out of hand and breaks often, which leads to frustration and dropping the idea completely.

What’s the worst thing about writing integration tests? DOM? Promises? Asynchronicity? Some strange framework API behavior? I’d say: all of them.

We’ve all been there. Element is not in the DOM but it should be. Request came back from the server too late (why weren’t you mocking your responses in the first place, huh? ;)). Promise is still unresolved. My app’s state changed but those changes haven’t propagated to all components yet. I changed my route’s hash or query parameter, and test runner didn’t catch that.

I got a false positive. I got a false negative. I got a race condition. I got inconsistent results. It works locally but my headless CI breaks.

Aaaaagr@#$%^&…! Damn you, Selenium. I’m done with you! I’ll just trust that I won’t make any mistakes and I won’t need integration tests. I’m sure I’ll be fine.

…One month later, on your company’s Slack channel…

Failed: awesomeJoe's build (#404; push in ImTooAwesomeForTests/ThisForSureWontBreakAnything (this_for_sure_wont_break_anything)

Refactored like 95% of the App, but I'm sure it's working and we'll be fine (b4d455 by awesomeJoe)

Failing tests: If you see this, you know that you messed up

The World Where Browser Is Not a Black Box

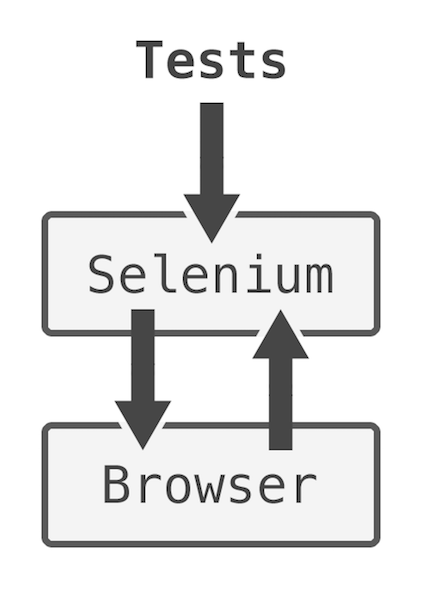

Protractor, Pioneer, Nightwatch.js, Intern and probably plenty of other testing frameworks out there in the wild use something which is called Selenium. Selenium is this magic black box that can understand your code and make browsers do what you ask them to do. Navigate to pages, click elements, get values, fill forms, control back/forward buttons, etc. But it being a black box can be problematic. Especially when testing asynchronous code.

What happens is the following: when your test runner issues a test, it asks Selenium to ask a browser and returns an answer to you. For example, if you want to know whether a given element is already rendered, you ask Selenium to ask a browser, which in the end checks the existence of an element, gives that answer to Selenium, which hands it back to you. In other words, it’s a middleware between your test runner and a browser. A black box.

It’s problematic, because we have no knowledge of the browser’s lifecycle, or “event loop.” We cannot wait for something to finish, know whether there are some unresolved promises or pending requests. If you ask Selenium for something, it’ll blindly go to the browser and fetch your answer.

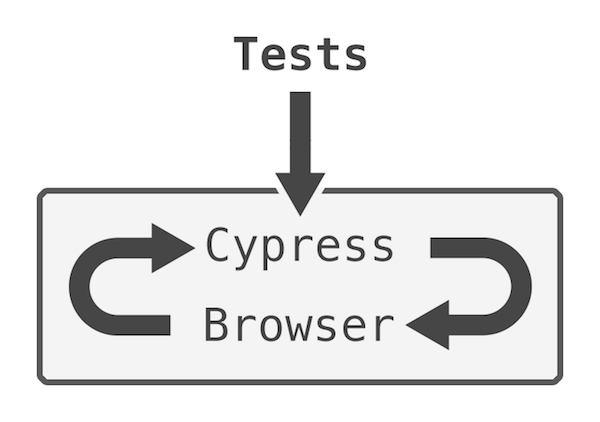

This is where Cypress shines. It’s a complete test runner, which lives inside a browser, alongside your own application code. It knows everything about browser state, event loop, as well as your application’s code.

This simplifies things a lot! It will politely wait for all the things to happen first, before issuing your test assertions. And even more, it will wait for the previous command to finish, before moving to another one, as everything is promise-based. You don’t have to use timeouts or any code like this anymore (thankfully, as timeouts are one of the biggest, if not the biggest source of race conditions and nondeterministic results).

”But wait, there’s more!” A thing that helped me even more is a perfectly-crafted debugging environment. Every test that you run in Cypress saves the browser’s state after every step. XHR Request, click, element query, location change. And you can go back and forth between those states, read the errors, debug an issue as you’d normally do in devtools, see the before/after screenshots. It’s so useful!

And yes, I know it’s closed Beta right now, but their team is really awesome, and they give away an access to everyone on their gitter.io channel. You should definitely come and say hi!

And I highly recommend watching the following official demo from the Cypress team:

Cypress.io - Overview Demo from Brian Mann on Vimeo.

Code for Tests

”Alright, show me the magic now!” Well, there’s no magic. The Cypress API is dead simple. But, ok, ok, here it is:

describe('Navigation', function () {

beforeEach(function () {

cy

.server()

.stubUserSession()

})

// your tests go here

}) What’s that stubUserSession, you ask? It’s our custom command we can create to make our code more DRY. Let’s see its content:

Cypress.addParentCommand('stubUserSession', function () {

const log = Cypress.Log.command({

name: 'stubUserSession'

})

cy

.route('POST', /session/, 'fixture:session/valid', { log: false })

.then(() => log.snapshot().end())

}) What a beautiful code! You create a command, give it a name, and ask to intercept all requests made to urls matching /session/ RegExp. When it finds one, it will serve our fixtures/session/valid.json file and prevent the browser from making a real request. It will give us 100% repeatability.

Now, it’s time for some actual tests.

it('should render all elements when user is logged in', function () {

cy

.visit('/dashboard')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-header]').should('exist')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-footer]').should('exist')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-sidebar]').should('exist')

}) I highly recommend using the [data-hook=*] pattern in all of your integration tests’ code. It’s a great way to separate concerns and specifically point out that it shouldn’t be touched in your HTML code.

<h1 id="page-title" class="make-it-shine">Hello World!</h1> You can query this element using #page-title or .make-it-shine selectors. But what happens when a designer comes to remove/change them? How can we know it’s not referenced somewhere?

<h1 id="page-title" class="make-it-shine" data-hook="page-title">Hello World!</h1> And now, you can simply use [data-hook=page-title], and it won’t break if someone changes id or a class.

Alright, back to the tests.

it('should display correct logo based on the current location', function () {

cy

.visit('/dashboard')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-dashboard]').should('exist')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-search]').should('not.exist')

.visit('/search')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-dashboard]').should('not.exist')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-search]').should('exist')

.go('back')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-dashboard]').should('exist')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-search]').should('not.exist')

.go('forward')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-dashboard]').should('not.exist')

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logo-search]').should('exist')

}) All those routes are client-side rendered, and the logo element reacts to an asynchronous change of the application’s state (which is event-based in this scenario). We can see a usage of location controls as we use back/forward buttons and assertions negation using not.

Let’s do something more complex. Let’s manually log in a user, verify redirect, go to a search section and log them out, making sure that they have been redirected, but this time to the login form.

it('should allow user to login, navigate and logout from the app', function () {

cy

.server({enable: false})

.visit('/login')

.server({enable: true})

.route({

method: 'POST',

url: /session/,

status: 200,

response: 'fixture:session/valid'

})

.get('[data-hook=login-form-username').type('john.doe@example.com')

.get('[data-hook=login-form-password]').type('verysecurepassword')

.get('[data-hook=login-form-submit]').click()

.url().should('match', /dashboard/)

.get('[data-hook=navigation-links-search]').click()

.url().should('match', /search/)

.route({

method: 'DELETE',

url: /session/,

status: 204,

response: {}

})

.route({

method: 'POST',

url: /session/,

status: 401,

response: 'fixture:session/invalid'

})

.get('[data-hook=navigation-logout]').click()

.url().should('match', /login/)

})It’s only that much code and it works like a charm. One note about those two route changes. The first one is stubbing our delete session request, which will be issued once we click the logout button. And the second one is overriding our previous valid session, changing it to invalid. Why? Because if you don’t do this, and your application is correctly validating the user’s authentication state, it would still think that you’re authenticated and most likely (if you implemented it that way), will redirect you back to a dashboard.

You may also be wondering about .server({enable: false}) and .server({enable: true}). Remember how we used stubUserSession in our beforeEach block? It applies to all tests. And if we were to omit turning off requests interception here, our .visit('/login') call would redirect us instantly to a dashboard, as the application would think that we are already authenticated and there’s no need to do this again. That’s why we change the order. We disable our server stubs, go to the login page and only then attach the stub again. This way our initial /login call won’t return an authenticated session. We could also do this by removing stubUserSession from beforeEach, and using it only when needed, or like this:

it('should allow user to login, navigate and logout from the app', function () {

cy

.route({

method: 'POST',

url: /session/,

status: 401,

response: 'fixture:session/invalid'

})

.visit('/login')

.route({

method: 'POST',

url: /session/,

status: 200,

response: 'fixture:session/valid'

})

...

})The last test I’d like to show you is verifying that we can change the location’s state (e.g. using HistoryAPI) directly, then through button clicks, and then using the back button, just for good measure. And making sure that other components, like search results can react to it.

it('should filter search results based on query parameters', function () {

cy

.stubSearchResults() // a stub that will return a 200 code response with 10 search results, 3 about places and 7 about people

.get('[data-hook=search-form-query]').type('Poland')

.get('[data-hook=search-form-submit]').click()

.url().should('not.match', /searchFilter=/)

.get('[data-hook=search-results]').children().should('have.length', 10)

.visit('/search?searchFilter=places')

.get('[data-hook=search-results]').children().should('have.length', 3)

.get('[data-hook=search-form-filter-people]').click()

.url().should('match', /searchFilter=people/)

.get('[data-hook=search-results]').children().should('have.length', 7)

.go('back')

.url().should('match', /searchFilter=places/)

.get('[data-hook=search-results]').children().should('have.length', 3)

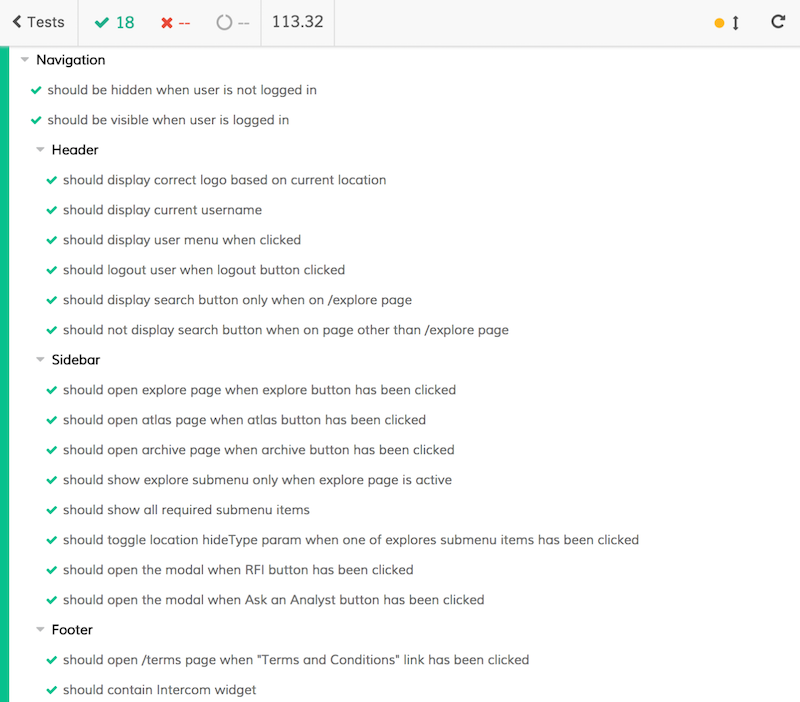

})Results of tests for one of the components in an app I’m working on right now:

I’ve shown you less than 10% of what Cypress can actually do. Give it a spin, it can be set up within minutes and doesn’t require any code changes in your application. It cannot get easier than this.

Yes, You Should Write Integration Tests

Because, why not? They are the best way to tell if your application is working correctly. They allow you to iterate quickly, refactor large chunks of your application without fear of breaking it, and they are really easy (and fun!) to write. It’s a great feeling to see your application being tested in real-time, seeing all the things being clicked, manipulated, forms filled and tests passing and changing color to green.

Don’t be frightened, they won’t bite you. They can only help you to be a productive and happy person. Your stress level will go down, your cortisol will drop, and you’ll be able to get better sleep, build more muscles and lose fat more quickly, which will result in you being healthier. Because health comes first. It’s basic logic. Write your integration tests. You’ll be healthier and live longer. Don’t thank me, just trust me. Been there, done that.

Want to be alerted when we publish future blogs? Sign up for our newsletter!